A health system under stress means the children will pay a price,warn child health advocates

A health system under stress means the children will pay a price, warn child health advocates

Inadequate medical treatment, children not being fully vaccinated, underfunded mental health services and the return of malnutrition are some of the impacts that severe budget cuts are having on children’s health and well-being, child health advocates warn.

On 24 and 25 January, a South African government delegation met the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) to report on progress towards the realisation of children’s rights.

Despite children’s rights being enshrined in the Constitution, key challenges remain – including significant gaps between the bold vision outlined in our laws and policies and delivery on the ground of services for children. And the recent budget cuts threaten to further erode children’s access to care.

In the context of an understaffed healthcare system, child health advocates have welcomed and echoed UNCRC commissioner Dr Philip Jaffé’s guidance to the South African government that “children should be exempted from fiscal tightness, or at least prioritised”.

Gaps are still evident after Covid

In a joint statement, the Children’s Institute, Child Health Priorities Association, South African Paediatric Association (Sapa) and Professor Ashraf Coovadia, head of the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health at the University of the Witwatersrand, emphasised that when the health system is under stress, children and children’s services are all too often forced to pay the price.

For example, they said, the Network of Child Health and Nutrition Advocates’ shadow report to the UNCRC described how child health staff are regularly diverted and redeployed to strengthen adult programmes such as HIV/Aids and TB or to address emerging crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

“That had a profound impact on children’s access to services at a whole range of different levels,” said Lori Lake of the Children’s Institute.

There are still gaps remaining in the coverage of critical child health services following the Covid-19 pandemic, which had a significant impact on children’s health services, the children’s health organisations said:

- Only 85.5% of infants are fully vaccinated, which is well below the national target of 90%;

- Only 80% of children with HIV have been tested, 55% of these are on treatment and 56% are virally suppressed. With the percentages of children’s testing, treatment and adherence falling below South Africa’s overall coverage of 93/78/90, and the Unaids 90/90/90 targets, the R1-billion cut in HIV/Aids funding is likely to further compromise children’s access to testing and treatment; and

- Child and adolescent mental health services are particularly thinly stretched and underfunded. While more than 10% of children have a diagnosable and treatable mental disorder, only one in 10 of these children is currently able to access care.

Professor Mignon McCulloch, an executive member of Sapa, said they were seeing worrying trends including:

- Children are not being fully vaccinated leading to outbreaks of measles in all nine provinces;

- Children are not receiving adequate medical treatment, including HIV treatment; and

- Children are often not even coming for medical follow-ups for chronic medical conditions because of their parents’ financial situation.

“We just feel that kids have had a bit of a tough time for the last couple of years and it’s time to say, let’s prioritise children, because children are our future,” McCulloch said.

Under-five mortality and neonatal mortality concerns

The under-five mortality rate is widely regarded as a key indicator of national health and development, and the extent to which a country is realising children’s rights to life, healthcare services, nutrition, water, social security and protection.

Despite a significant decline in under-five mortality following the roll-out of the programme to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, progress has stalled, and there are signs that child mortality may be rising.

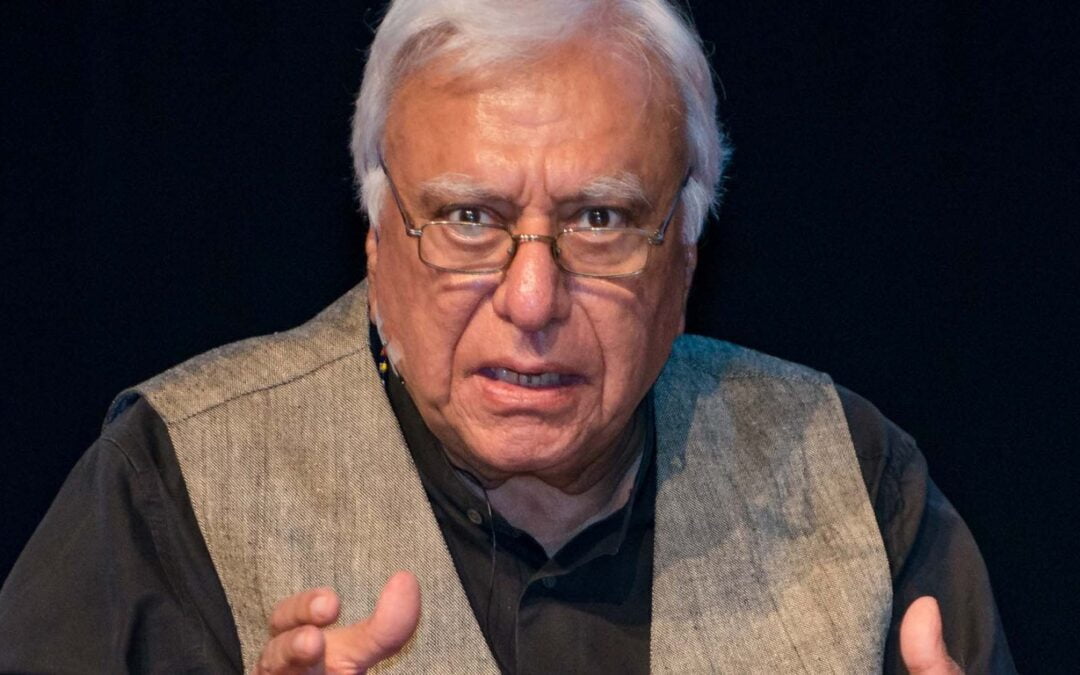

Professor Mignon McCulloch, executive member of the South African Paediatric Association. (Photo: TTS 202 / Wikipedia)

“We were already flagging concerns back in 2019 that without renewed efforts, we were likely to struggle to reach the SDG [Sustainable Development Goal] goal in terms of under-five mortality,” Lake said.

Neonatal mortality rates – when a baby dies in the first 28 days of life – are also a concern.

“The neonatal mortality rate in South Africa is 12 deaths per 1,000 live births and that has been pretty much the same, at least for the last 10 years, which means we need to invest more in neonatal care,” Lake said.

“The shadow report to the UN indicated that we have severe shortages of nurses in neonatal care, we don’t have enough neonatal ICU beds, we don’t have enough paediatric ICU beds, and this is compromising critical care for very, very sick children.”

Children paying the price for austerity measures

Ute Feucht, chairperson of the Child Health Priorities Association, said human resources were essential to providing child healthcare services.

“The issue is that maternal and child health spending is not ring-fenced. What we are seeing now is that the funding is just cut everywhere, which means there are fewer and fewer resources for human capacity,” she said.

Feucht said this was a “huge concern” in the paediatric and child health community as posts remain vacant.

“Many of the challenges that we’re talking about in terms of child health services are in many ways invisible. You only see the effects once the programme collapses, or has inadequate coverage. For instance, as immunisation coverage drops, then one starts seeing outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles,” she said.

“We need the human resources to be able to service the children when they come to clinics. We need the nurses, the doctors, the vaccines, all of it. There need to be enough health workers there to actually make sure that the service can be provided. It also doesn’t help if people need to queue at 5am to maybe be seen many hours later,” Feucht said.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Western Cape health professionals make united appeal for ‘catastrophic budget cuts’ to be halted

If budget cuts are necessary, then they should never be made at the expense of children’s health, in keeping with guidance from the UNCRC, McCulloch said.

“Children are our future and so we feel that children’s health should be ring-fenced so that we can maintain children’s health,” she said.

Inflationary pressure

Rising costs of living are also having an impact on children’s health.

“We know that food and fuel prices are going up, and one in five children need to travel more than 30 minutes to get to a hospital. Children who are sick can go into shock quickly so it is crucial that they can access health facilities rapidly as there is a real risk of mortality and even long-term disability as a result of delayed treatment,” McCulloch said.

“If they’re not getting fed sufficiently, we know malnutrition carries a high mortality, and if they’re not getting access to healthcare or there are long waiting lists for children’s surgery, children may succumb from treatable conditions. Children get sick quickly but also recover really quickly, and so there are lots of quite basic concerns that we have as paediatricians.”

Feucht said that even though the country was experiencing a financially difficult time, it was still important to prioritise children and strategise about how to get the most out of the available money.

“Children are getting hammered. Yet they have a constitutional right to access quality healthcare in our country, and we should be able to provide services to our children even in difficult times,” she said.

“As a country, we need to prioritise children as a non-negotiable in terms of access to proper care, healthcare, family care and nutrition”.

Lake agreed and said the health system should ramp up its response and care for pregnant women and young children by strengthening outreach services and community-based services.

“It is a time for health to do more rather than less, and yet what we’re seeing with the austerity cuts, is that posts are getting frozen and the health workers running those services are struggling to maintain a service with less,” she said.

The remaining staff carries the same burden of care, increasing the risk of burnout, errors and compromised care, Lake said.

“Our concern is that cuts are going to become so deep that they fundamentally compromise the health, care and survival of children.”

Lake, Feucht and McCulloch all reiterated that they recognised the difficulties that the government and provincial authorities were facing.

“As health departments, it must be very tough to have your budget cut. But what we are saying is that we are watching children run into trouble and children often don’t have a voice,” McCulloch said.

Malnutrition increasing as families suffer strain

Lake said it was equally important to note that families were also under strain.

“We watched Covid have a devastating impact on the economy, rising food, poverty, rising unemployment, rising hunger, and that picture has persisted even post-Covid and that has been driven by ongoing high unemployment, as well as rising food and fuel prices. So we know that families are struggling to feed their children,” she said.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Child malnutrition in the Eastern Cape ‘qualifies as a disaster’

“It means it is a lot harder for families to care for their children, and they’re having to make these really difficult decisions between ‘do I have enough money to feed my children? Or am I going to pay for transport to access healthcare services?’” Lake said.

The national incidence of severe acute malnutrition increased by 23% from 2018/19 to 2022/23, and nearly half of the children who died in hospital in 2022 were either moderately or severely malnourished, according to data from the Child Healthcare Problem Identification Programme.

“We are seeing malnutrition which we haven’t seen for quite a long time. It’s definitely worse than it was before,” McCulloch said.

“As clinicians and as doctors looking after children, it’s quite tough to see malnutrition creeping back in, so we are very worried about the health of children. It is something we haven’t seen for years,” she said.

The way forward

In 2020, in its ruling against the closure of the National School Nutrition Programme during the Covid lockdown, the Gauteng Division of the High Court in Pretoria noted that once a state has taken on such an obligation to fulfil children’s rights, it cannot “backtrack”.

It also affirmed the UNCRC’s General Comment 19 on Public Budgeting for Children’s Rights, which stipulates that even in times of economic crisis, “regressive measures may only be considered after assessing all other options and ensuring that children are the last to be affected, especially those in vulnerable situations”.

Lake said this illustrated that rights-based arguments also carried legal weight in South Africa and that while budget cuts might indeed be necessary, these should never be made at the expense of children’s health.

“What we are really hoping is that the Department of Health will issue some very clear guidelines from the national office and from the provinces to ensure that children’s services are protected and that’s one of the criteria that is held in mind as the departments consider how to implement these austerity cuts,” Lake said.

McCulloch said this was an appeal to the government to protect children and that maternal and child health services needed to be prioritised and protected. Achieving this, especially when the country was experiencing financial difficulties, would require some innovation and thinking out of the box, including possible public-private partnerships.

“We are very, very happy to work with the government on this, we are just saying that children’s health needs to be protected and prioritised.”

McCulloch said the government needed to do everything it could to improve children’s access to healthcare.

“I think the bottom line is that public health people are worried and paediatricians are worried as well. I saw a kid this morning with severe acute malnutrition and I said to my students I haven’t seen a case this severe in a long time. It’s really quite sobering to see that.”

Department responds

Health Department spokesperson Foster Mohale said the current budget cuts do not affect child immunisation because the country has vaccines for the Expanded Immunisation Programme, and the outbreaks of diseases such as measles are mainly because of low vaccine coverage (unvaccinated children).

Mohale also said there is no proof of inadequate medical treatment including for HIV.

“Patients who receive chronic medication are always reminded and encouraged to enrol for the Central Chronic Medicines Dispensing and Distribution programme which enables patients to collect chronic medication at any external pick-up-point closer to their homes or workplace free of charge other than health facilities. This programme reduces travelling costs and waiting times at health facilities,” he said.

“The Department of Health and provincial health departments prioritise essential services during budget cuts or austerity measures. There is no proof of children being at risk”. DM

Be true to science and kind to patients, says healthcare giant Jerry Coovadia

SAJCH NEWS Vol 17