Advocates call for child health services to be protected from from austerity cuts

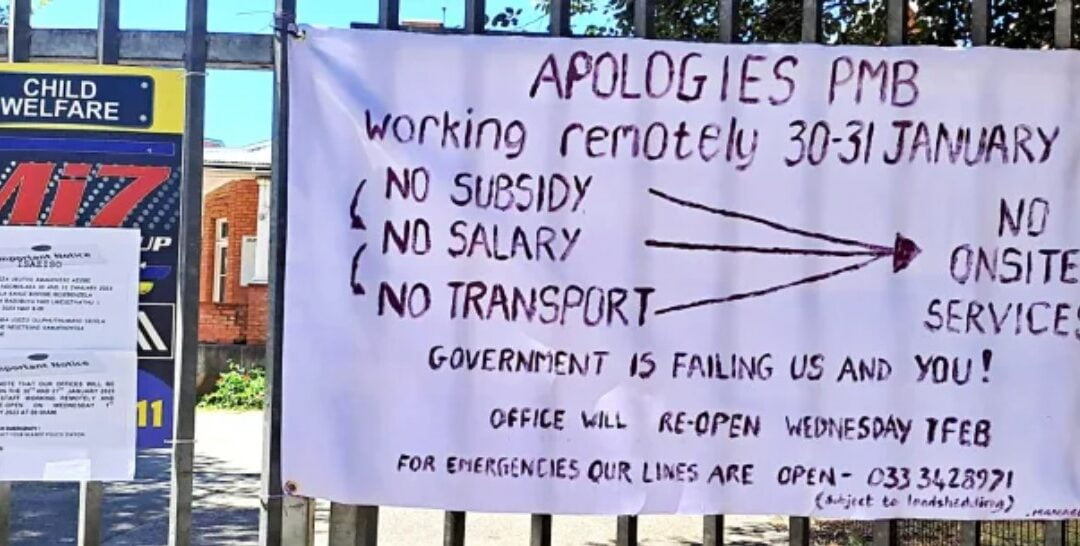

Pietermaritzburg Child Welfare depends on subsidies from the KZN social development department, which are always late, causing a cash-flow crisis. It is also reported to be waiting on lottery funding, which is also late. The consequences can be catastrophic for vulnerable children. (Photo: Supplied)

The Child Health Priorities Association released a statement today, addressed to the government, raising the alarm about the impact of austerity and budget cuts on the lives of South Africa’s poorest children.

The statement is unusual and important because its signatories include all the major child advocacy organisations in South Africa, academics and paediatric departments of five South African universities and more than 100 professors, doctors and other allied health workers with an interest in child health and well-being.

The statement comes on the eve of the 2023 State of the Nation Address and, later in February, the annual budget.

Its authors say it has been necessitated by growing evidence of the harm to children caused by Covid-19, unemployment and violence (among other things). Child hunger and malnutrition is something that Maverick Citizen has been reporting on consistently in recent months.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Desperate children are eating cow dung to line their stomach for lifesaving medicine, say researchers”

Experts say a malnutrition epidemic is growing and will have an impact on the life outcomes of children for generations to come.

Similarly we have received reports of child health and social services stretched beyond breaking point at a terrible cost to children.

The signatories point out that in the context of South Africa’s Constitution promising “all children” the right to “basic nutrition, shelter, basic healthcare services, and social services”, the government should be increasing and improving child welfare services, rather than undermining them.

Given the importance of this statement we publish it in full below. For more information visit the Child Health Priorities Association website or call Professor Ute Feucht on 072 428 0425, Professor Neil McKerrow on 082 449 2833 or Lori Lake on 082 558 0446.

Statement

According to Statistics South Africa, one in every three people in South Africa are children under the age of 18. If we, as South Africans, make the right investments to promote their optimal health and development, our young population has the potential to transform our country and drive social and economic development.

Yet, as explained in this Advocacy Brief by the Children’s Institute at UCT, our youngest citizens are disproportionately concentrated in the poorest households and are highly vulnerable to shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the current economic recession.

At the Child Health Priorities Conference, hosted at the University of the Witwatersrand in late November 2022, we noted with concern Treasury’s intention to cut social spending, as outlined in its October 2022 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement. This includes cuts to health care services and social assistance. These cuts threaten to undermine the provision of essential child health services whilst simultaneously pushing more children even deeper into poverty.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Medium term budget is taking from the mouths of babies, children’s organisations claim. Daily Maverick, 27 October 2022”

A call to action

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child has issued clear guidance that States should not introduce retrogressive measures such as austerity budgets that compromise children’s rights to health, survival and development.

We therefore call on health professionals, managers and administrators at every level of the healthcare system to take proactive steps to safeguard and ring-fence budgets for child health services to ensure that the proposed austerity measures do not introduce retrogressive measures or erode children’s rights to health care services.

Here we draw on the latest science, economic and legal arguments to support the call for the protection and ring fencing of budgets for child health services.

(1) Children’s health and access to healthcare services are already compromised

- Even before the pandemic, there is evidence from the Medical Research Council and Department of Health that many South African children were failing to thrive with more than a quarter of children under five years old stunted in their growth and development;

- The Covid-19 pandemic orphaned nearly 150,000 children while the accompanying recession pushed a further 1.5 million children into food poverty – so that by 2020, 4 in every 10 children lived in households that could not afford to meet their children’s nutritional needs (Hall K. Poverty, unemployment and social grants. In: Tomlinson M, Kleintjes S & Lake L (eds) South African Child Gauge 2021/22.);

- Post-Covid, rising food and fuel prices have further eroded children’s food security, nutritional status, and access to healthcare services;

- The reduced utilisation of routine primary healthcare services seen at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic has persisted and is associated with low immunisation coverage as evidenced by the recent outbreaks of preventable diseases such as measles and whooping cough.

(2) The science

There is now incontrovertible evidence that early life experiences fundamentally determine the developmental origins and trajectories of health or disease across the life course, and across generations. With this knowledge, there is a growing recognition that it is most effective – and cost-effective – to intervene early in life to prevent illness and promote optimal health and development.

For example:

- Published research has shown that 50% of mental disorders have their onset before the age of 14 years, and 75% before the age of 24 years, and prevention and early intervention in childhood and adolescence were identified as “the most promising investment in population mental health” by the Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health;

- Similarly, the “slow violence” of the triple burden of child malnutrition (undernutrition, obesity, micronutrient deficiencies) is fuelling the acceleration of non-communicable diseases that threatens to overwhelm the healthcare system.

In both cases, it is more effective – and cost-effective – to invest in prevention and early intervention – even preconception – where efforts to ensure the health and well-being of adolescents prior to childbearing has the potential to kick-start a positive intergenerational cycle of human capital development.

(3) The economic arguments

These investments in child and adolescent health will reap a triple dividend –for the children of today, for the adults they will become tomorrow, but also for the next generation of children. For example, a recent systemic review (Long-term economic outcomes for interventions in early childhood: protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open 2020) noted that:

“Investment in early childhood generates positive returns, for the child, the family and the wider community. Benefits to children in the short term include the development of resilience, improved cognitive skills, reduced school absenteeism and reduced risk of disease. Longer term outcomes include better employment pathways, improved health, reduced dependency on welfare (including social services, incarceration and juvenile justice) and reduced inequality.

“This is particularly true for children unable to fulfill their full potential, due to poor health, lack of opportunities to learn and/or deprivation of care. Improving early child development has the potential to improve national productivity and gross domestic product. It is not simply a ‘nice to have’ in an ideal world. Conversely, the cost of failing to adequately support children has implications for the child, community and the national economy.”

While interventions initiated in the first 1,000 days of life have been shown to yield the highest economic returns, particularly for children experiencing adversity; these investments need to be sustained throughout childhood into adolescence to ensure the benefits are not eroded over time.

The second decade of life is a time of risk, but this period of rapid development also offers another opportunity to enhance outcomes and set the trajectory for lifelong health and development. Interventions to support adolescents’ physical, mental and sexual health during this period have been shown to yield up to a 10-fold return on investment by saving lives and reducing unintended pregnancies.

(4) Global commitments and evidence-based guidelines

The emerging science and economic arguments have informed a shift in global health strategy from a narrow focus on survival to a broader thrive agenda – as outlined in the Global Strategy for Women’s, Adolescents’ and Children’s Health, the Nurturing Care Framework, Global Accelerated Action for Adolescents, and the World Health Organization’s quality standards for maternal, newborn and paediatric services to ensure access to safe, effective, quality and affordable care.

(5) The legal arguments

Section 28 of our Constitution recognises children’s vulnerability and the State’s obligation to uphold their best interests and provide a higher standard of care and protection. For this reason, children’s right to basic health care services is immediately realisable and is not subject to progressive realisation or limited by available resources.

The state is therefore obliged to put in place definitive measures to give effect to children’s right to health care services. This includes adopting appropriate laws, policies and programmes; providing the necessary budget and resources; ensuring the design and delivery of health care services upholds children’s best interests; and improving child health outcomes across a range of indicators.

In addition, Article 24 (2) of the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child states that government must prioritise child health within the health plan for the general population, and in its General Comment 14 on the right to the highest attainable standard of health the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights stipulates that these health goods, services and programmes should be available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality.

No retrogressive measures

In 2020, the Gauteng High Court (in Equal Education and others v Minister of Basic Education and others (17 July 2020), a ruling against the closure of the National School Nutrition Programme) noted that once a state has taken on such an obligation, it cannot ‘back-track’.

The High Court then affirmed the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment 19 on Public Budgeting for Children’s Rights which stipulates that states “should not take deliberate regressive measures in relation to socio-economic rights” and that even in times of economic crisis, “regressive measures may only be considered after assessing all other options and ensuring that children are the last to be affected, especially those in vulnerable situations”:

“State parties shall demonstrate that such measures are necessary, reasonable, proportionate, non-discriminatory and temporary and that any rights thus affected will be restored as soon as possible. States parties should take appropriate measures so that the groups of children who are affected, and others with knowledge about those children’s situation, participate in the decision-making process related to such measures. The immediate and minimum core obligations imposed by children’s rights shall not be compromised by any retrogressive measures, even in times of economic crisis.”

In conclusion

While we recognise that resources are constrained, but budget cuts should never be made at the expense of child health. All too often child health services are cut because children have no voice, while civil servant salaries and parliamentary perks remain untouched. Cutting child health services and social assistance in the context of rising poverty and hunger, constitutes a clear violation of children’s rights and a shameful betrayal of the very central pillar of our Constitution.

The child’s name is Today

The child cannot wait.

Right now is the time the child’s bones are being formed,

blood is being made, senses are being developed.

To the child we cannot answer “tomorrow”

The child’s name is Today.

(Gabriela Mistral, Nobel Prize-winning poet from Chile)

Issued by the Child Health Priorities Association Executive Committee

Organisational endorsements:

Centre for Child Law, University of Pretoria

Child Problem Identification Programme (PIP), Executive Committee

Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town

ChildSafe South Africa

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services Strengthening Team

Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of the Witwatersrand

Department of Paediatrics and Childhood, University of Pretoria

Department of Paediatrics, Mitchells Plain Hospital

Groote Schuur Hospital Adolescent Centre of Excellence

Harry Crossley Children’s Nursing Development Unit, University of Cape Town

Healthy Living Alliance (HEALA)

Institute for Life Course Health Research, University of Stellenbosch

Mowbray Maternity Hospital, Neonatal Medicine Department

PaedsPal

Paediatric Students Society, University of Cape Town

People’s Health Movement of South Africa

Rural Health Advocacy Project

Section27

South African Civil Society Organisation for Women’s, Adolescent and Child Health (SACSOWACH)

South African Paediatrics Association

Individual endorsements

Professor Ute Feucht, Department of Paediatrics, University of Pretoria

Dr Wiedaad Slemming, Division of Community Paediatrics, University of the Witwatersrand

Professor Haroon Saloojee, Division of Community Paediatrics, University of the Witwatersrand

Professor Ashraf Coovadia, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of the Witwatersrand

Professor Neil McKerrow, Departments of Paediatrics, Universities of Cape Town and KwaZulu-Natal

Professor Shanaaz Mathews, Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town

Lori Lake, Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town

Professor Maylene Shung-King, School of Public Health, University of Cape Town

Professor Mark Tomlinson, Institute of Life Course Health Research, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Dave le Roux, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Mandy Wessels, Executive Chairperson Child PIP

Dr Yogan Pillay, Department of Global Health, Stellenbosch University

Dr Denise Evans, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office, University of the Witwatersrand

Nozipho Musakwa, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office, University of the Witwatersrand

Emeritus Professor Andrew Argent, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Professor Petrus de Vries, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Cape Town

Dr Chantell Witten, Centre of Excellence in Food Security, University of the Western Cape

Dr Joan van Niekerk, National Representative for Children on the Civil Society Forum of South African National AIDS Council

Dr Diane Gray, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Catherine Mathews, South African Medical Research Council

Dr Max Kroon, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Thandi Wessels, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Rowan Dunkley, General Paediatrician, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital.

Dr Jaco Murray, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Paarl Hospital.

Dr Nomlindo Makubalo, Department of Health, Eastern Cape

Dr Gabriel Urgoiti, RX Radio

Nzama Mbalati, Health Living Alliance (HEALA)

Prof Regan Solomons, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Prof Adrie Bekker, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Prof Angela Dramowski, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Gugu Kali, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Sandi Holgate, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Lisa Frigati, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Krisna Keyser, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Jameel Busgeeth, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Angeline Thomas, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Minette Maree, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Nomusa Mfeka, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Muneerah Satardien, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr RC Krause, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Audrey Sullivan, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Pippa Durr, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Netta van Zyl, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Odette Viola, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Dr Chane Kay, Paediatrics Karl Bremer hospital

Dr Natasha O’Connell – Khayelitsha district Hospital

Jane Booth, retired nurse at Breatheasy Programme

Dr Rene Nassen, Department of Psychiatry, University of Stellenbosch

Dr James Porter, False Bay Hospital

Dr Shamiel Salie, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Louise Cooke, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Ariane Spitaels, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Graham Spittal, Department of Paediatrics, Mitchells Plain Hospital

Emeritus Professor Louis Reynolds, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Professor Rina Swart, DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security, University of the Western Cape

Dr Claire Procter, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Andrew Redfern, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Stellenbosch

Professor Alan Davidson, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Phumza Nongena, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Marja Wren-Sargent, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Professor Heather Zar, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Thandi de Wit

Professor Michael Levin, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Marc Hendricks, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Wendy Vogel, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Kate Webb, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Aleya Remtulla, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Professor Marco Zampoli, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Peter Nourse, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Zakira Mukkadem-Sablay, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Michelle Meiring, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Sanja Nel. SAMRC Maternal and Infant Health Care Strategies Unit, Pretoria

Dr Helen Mulol, SAMRC Maternal and Infant Health Care Strategies Unit, Pretoria

Dr Yaseen Joolay, Division of Neonatal Medicine, University of Cape Town

Dr Tanya Doherty, Health Systems Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council

Professor Refiloe Masekela, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Kate Baume, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Ben van Stormbroek, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Gill Shermbrucker, Department of Paediatrics, Victoria Hospital

Dr Kirsten Reichmuth, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Sydney Bongani Nkosi, Niemeyer Memorial Hospital

Professor Michael Hendricks, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Emeritus Associate Professor Tony Westwood, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Professor Chris Scott, University of Cape Town Clinical Research Centre

Professor Mignon McCulloch, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town

Emeritus Professor Marian Jacobs, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town

Professor Rajendra Bhimma, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University to KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Nox Mbadi, Addington Hospital

Lucy Jamieson, Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town

Nonhlanhla Mtolo, Children’s Nursing Development Unit, University of Cape Town

Dr Lyndall Gibbs, PaedsPal

Professor Minette Coetzee, Harry Crossley Children’s Nursing Development Unit, University of Cape Town

Dr Papani Gasela, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Cape Town

Professor Sharon Kleintjes, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, University of Cape Town

Dr Kimesh L Naidoo, KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Radhika Singh, KwaZulu-Natal

Professor Moherndran Archary, KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Visva Naidoo. KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Ayanda Msomi. KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Leanne Munian, KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Gugulethu Buthelezi, KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Zohra Banoo, KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Nomgcebo Mzizana, KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Yasha Kannigan, KwaZulu-Natal

Bright Makhubedu, PaedSoc (Paediatric Student Society), University of Cape Town

Jane Vos, Harry Crossley Children’s Nursing Development Unit, University of Cape Town

Dr Rajas Naidoo, DCST West Rand District

Dr Romolo Naidoo, DCST Ugu District

Dr Cindy Stephen, Child PIP EXCO

Dr Mark Patrick, Child PIP EXCO

Dr Kim Harper, Child PIP EXCO

Dr Lesley Bamford, Child PIP EXCO

Dr Ndaye Kapongo, KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Jodi Wiles, KwaZulu-Natal

Dr Nomonde Bhengu, KwaZulu-Natal. DM/MC